What is the platform economy?

By 2025, the platform economy will represent 335 billion dollars whereas it weighed only 15 billion in 2014 according to the firm Pwc (2015) .

Today, with the rise of new information and communication technologies, this uberisation is at the heart of our society and at the center of debates . Indeed, everyone has already got in touch with Airbnb, leboncoin, Facebook or even Uber. However, the term ” platform ” remains rather vague for the general public.

Platforms can be defined as services performing an intermediary function . Their characteristic is to offer goods, services to customers which are produced, made available or sold by contributors who are most often individuals , but also professionals .

Thus, the platforms play the role of trusted third parties whose activity is centered on visibility, advertising, rating or even payment security.

The advent of platforms marks a turning point with traditional firms. Indeed, where the large managerial firm, engine of capitalism was characterized by the concentration of assets, the internationalization of activities and a hierarchical functioning , platforms are, as Jensen Meckling underlined, a simple knot of contract between workers, capital etc…?

Thus, where the managerial company organized and transformed the work , the platform contracts, outsources, and remote control. It is no more than a company “without assets” refocused exclusively on its core business. The work is no longer designed by the platform, which is no longer responsible for it: it has left the company.

Platform capitalism takes us back to the pre-industrial domestic system

Aurélien Acquier, professor at ESCP Business School.

It is indeed possible to glimpse in the development of platforms a return to the domestic system which seemed to have been swept away by the first industrial revolution . Indeed, there are many common points between the two economic models such as:

- The fact that it is the worker who brings the necessary capital to the activity.

- The disappearance of a workspace managed by the employer.

- The hierarchical independence (but the economic dependence) of the workers.

- The difficulty of thinking about a form of collective (or union) action and representation.

- The difficulty of defining the boundary between domestic, productive and professional spheres.

- The existence of a plural work with side activities (reminiscent of the “Slashers”, these workers who combine several trades) rather than a single full-time activity.

- Individual self-organization (individuals themselves determine their degree of engagement on the platform).

The platform economy: a model at the origin of debates and tensions

It’s not hard to be competitive when you don’t respect anything.

This quote from investment banker Philippe Villin is a good illustration of the conflicts engendered by the rise of the platform economy.

Platforms can harm consumers. One of the annoying subjects is undoubtedly confidentiality. Indeed, if collecting consumer data is an important source of gain for platforms, it can also be seen as an encroachment on privacy.

In addition, some platforms require providers to make information about themselves or their environment publicly available on the Internet. An offer for renting a private room, for example, requires photos of one’s own apartment to be visibly uploaded to the platform for everyone to see.

Another debatable point is the lack of warranty . Indeed, most sharing economy platforms only act as intermediaries, but do not guarantee the quality of the goods or services offered. Therefore, users should rely entirely on reviews left by other users .

Finally, some households denounce a marketing process initiated by the platforms. The latter would convert free services into a paid model. This is particularly the case with couchsurfing, during which visitors can spend the night for free in a service provider’s apartment. This practice has seen its number of users drop drastically in favor of airbnb and similar providers. But it is above all competing companies that complain about the rise of collaborative.

First, there have been fierce challenges from companies competing with the platforms. They denounce unfair competition linked to differences in obligations in terms of taxes, contributions and regulations. Digital platforms, due to their outsourcing, bear almost no cost, which allows them to set extremely attractive prices. Thus, the fact that Uber drivers do not need a license (costing €200,000 ) to exercise their profession unlike taxis has led to demonstrations bringing together hundreds of taxi drivers, particularly in Paris and Reims. Another example, Zervas et al. (2016) estimated that Airbnb reduced hotel revenue by 8-10% in Texas.

In addition, digital platforms like Facebook are developing on two-sided markets (one side occupied by individuals, the other by businesses) on which network effects are strong.

From then on, we will witness a self-reinforcing effect according to Laffont and Rocher . Indeed, the more companies, in particular advertising or video games, publish content, the more individuals join the market and the more individuals there are, the more companies are encouraged to publish content: it is a virtuous circle . Thus, these digital platforms often find themselves in a monopoly situation. Which can be a problem if it starts erecting barriers to entry or setting abnormally high prices.

Finally, another aspect that is still too neglected concerns the rights of workers within the platforms. The latter are not employed on a permanent basis but earn their living as self-employed persons. Thus, they are deprived of the core of rights that protect employees, such as trade union rights, legislation on working hours and working conditions, and protections against harassment and discrimination.

In addition, they benefit from the social security coverage of the self-employed , which is less favorable than that of employees, even though their working conditions and remuneration as well as their dependence on digital platforms expose them to significant risks . Thus, the rise of platforms can be synonymous with growing inequalities because workers combine sometimes indecent remuneration with work that is as intensive as it is unstable (Deliveroo).

Not everything is to be thrown away in the platform economy

Platforms as a source of opportunities for suppliers and buyers. Even if there are points to criticize, it is undeniable that the platforms render great services to consumers. Accessible at any time, quickly, at unbeatable prices (purchasing power gain) their services obviously make our daily life easier.?

In Paris, the price of a hotel was around 200 euros , while it cost an average of 100 euros in Airbnb .

Moreover, a point that is not often mentioned, the activity of the platforms is very well reconciled with the challenge of sustainable development. Indeed, thanks to the shared use of cars or the reuse of used goods, fewer goods are produced, which saves resources and, ultimately, protects the environment (although this must be taken into account). realize that consumption may increase due to lower prices).

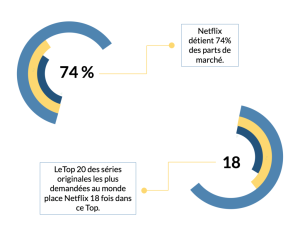

If we turn to the supply side , the platforms offer the opportunity to set up innovative business models , as illustrated by the examples of Airbnb , Uber and the Netflix streaming platform. If successful, sensational winning opportunities await. In addition, this new business model has the advantage of opening up new economic fields and reaching customers who might not previously have been enthusiastic about the company’s offer.

The platform economy also seems to provide the flexibility that so many economists have been hoping for. Indeed, in a knowledge economy (Jean Tirole, 2014 Nobel Prize winner and Olivier Blanchard), it is essential to have a flexible labor market. The platforms allow hiring and firing at no cost and almost instantaneously, allowing the process of creative destruction to unfold optimally.

At the same time, the platforms offer an alternative to traditional employment that is more suitable for some workers because it is possible to shape their working hours themselves.

Could the solution be adaptation?

In view of its growing momentum, the platform economy is becoming the new economic paradigm of our society.? Knowing this, can we eternally ignore it? Wouldn’t composing with it make it less controversial?

- The creation of a new status for self-employed platform workers.

Creating a new status allowing the worker to regain rights and quality social coverage seems essential.

According to DARES, this avenue has been explored in the United States by two economists, Alan Krueger and Seth Harris , who are campaigning to put an end to this legal uncertainty . This status would allow workers to come together to negotiate their working conditions , which is currently impossible for the American self-employed , but also to allow access to advantages concerning social protection or even the guarantee of protection against discrimination. or harassment .

Organize an overhaul of social rights and the tax system.

Another problem is social rights . Indeed, in France in particular, these rights are attached to jobs, which therefore poses complications for platform workers who are not associated with a single job .

My father had one job all his life, I will have six jobs in my life, and my children will have six jobs at the same time.

Robin Chase

Two solutions are considered:

- Link rights not to employment but to the active person .

- Broaden the logic of assistance by making these rights universal as Gazier, Périvier and Palier recommend in Refounding the social protection system.

- Adapt platform taxation systems as well as those concerning the taxation of platform income.

- The platform model, and more generally the digital model, facilitates the tax optimization of companies because the immaterial nature of the activities makes it more difficult to define a tax base.

The revenues of the platforms also largely escape the deduction of social security contributions. In France, according to a survey conducted in 2014, only 15% of the income of individuals from the platform economy is declared to the tax authorities. Under-declaration results from both a lack of clarity in the forms and the absence of control mechanisms.

Conduct a new competition policy.

Faced with tensions due to a certain amount of unfair competition, revising competition policy seems essential. Public authorities should adapt their analytical tools to better identify the collaborative economy .

Escadrille Toulouse Junior Conseil: digitize to better adapt

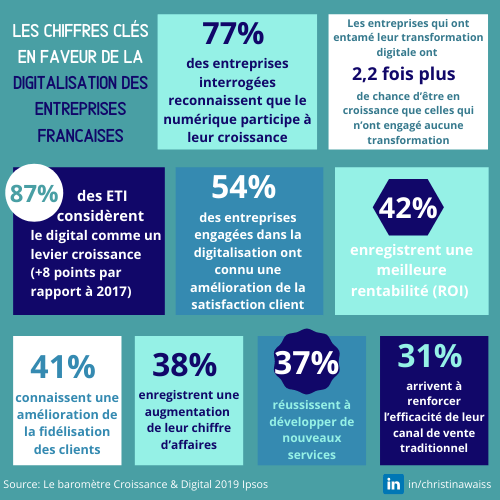

2/3 of merchants were not digitized during confinement and 40% saw their turnover halved.

Based on this observation, ESCadrille has become aware of the importance of digitalization at the present time. Not only does it allow you to adapt and bounce back more quickly, but also and above all it allows you to launch innovative projects . Today, most of the companies that stand out are precisely companies founded around this process of digitalization . Among them, Netflix , Airbnb or even Doctolib . More broadly, 42% of companies recognize that digitalization has increased their profitability . It is therefore a major driver of growth .

Thus, ESCadrille has reinvigorated its digitalization service, particularly during confinement, with a project aimed at supporting merchants in their digitalization. This support takes place in 4 steps :

- An audit of the existing

- Developing a digitalization strategy

- Assistance in finding aid and grants

- Implementation of training around digital tools

Having a real expertise in the mastery of digital tools with in particular the existence of a pole dedicated to this field , ESCadrille will be able to perpetuate your activity by digitizing it.

So, it’s up to you to take your revenge on the past months by calling on a motivated team, and eager to support your projects as well as possible.

Article written by MAXENCE RIVOIRE, 2021.